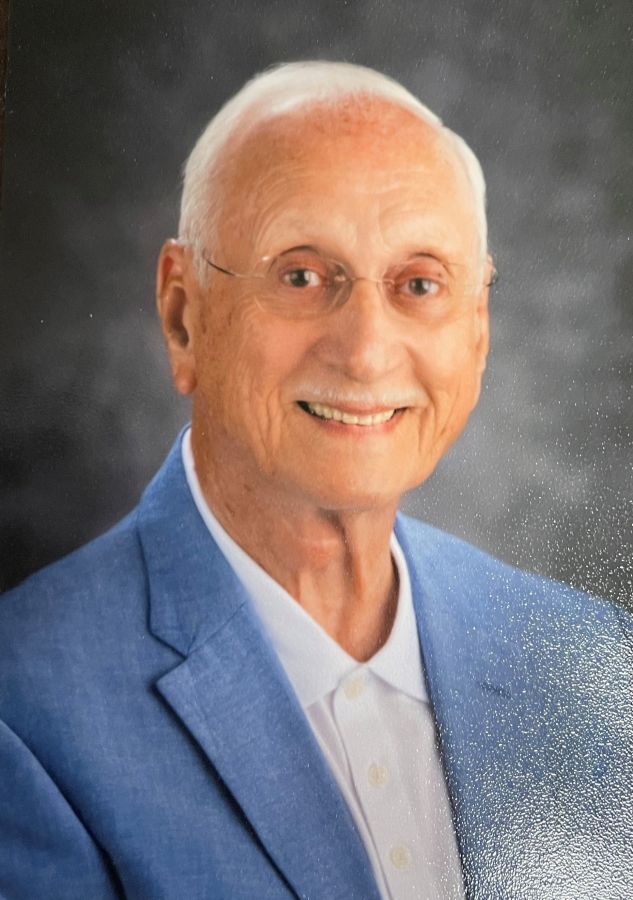

In loving memory of

Hertzel Phillip Aron

January 13, 1931 - October 8, 2021

The afternoon when everything changed - when Hertzel Aron learned that lymphoma had invaded his body and, at nearly 91, he wasn't going to fight it - he delivered very specific instructions.

He had a list of loved ones he wanted to be the first to know. He also wanted them to know:

• They could come see him, as long as they didn't bring anything.

• Don't pity him.

• "Tomorrow is Yom Kippur. Pray for me."

The scene captures much of his essence: A sharp, decisive mind. Love of family. Putting the feelings of others first. And treasuring his Jewish roots.

***

Hertzel Phillip Aron was born in Goose Creek, Texas, on Jan. 13, 1931 - squarely in the middle of the Great Depression - to turn-of-the-century immigrants Esidor Aron and Orina Wilkenfeld Aron.

Esidor and Orina's family already included Merilee, Peggy and Sidney. Hertzel remained the baby for seven years, until Bernadean arrived.

Four days after Hertzel turned 10, Esidor died. He was 46.

When Hertzel was in eighth grade, bullies beat him up for being Jewish. (So Jewish that his family was among the founders of the synagogue in Goose Greek, now known as Baytown.) Hertzel told his mother he didn't want to return to that school. The whole family ended up moving to Houston.

He went to college at the University of Texas, and loved it. He played oboe in the marching band (including a trip to the Orange Bowl in Miami on New Year's Day of his freshman year) and enjoyed being in Tau Delta Phi fraternity. Yet after two years, he felt guilty about having so much fun when he could be living at home and working. So he returned to 1721 Wichita Street, living on the top floor of a triplex with his mother and younger sister.

Taking classes at the University of Houston at night, he spent his days at Altman's Furniture. He quickly earned their trust, sometimes even running the store. He also saved enough money to buy a canary yellow Studebaker convertible.

A year later, as Hertzel neared graduation, he learned of a trip to Europe for students. It included visits to France, Italy, England, Ireland, Scotland, Germany, Switzerland and Luxembourg.

"I didn't have the money to do it," he said. "But I had the car and it was paid for. So I sold it and that financed that trip."

Upon returning, he bounced between a few different things. Around this time, he turned 21 and - with the U.S. fighting the Korean War - he went for his military physical.

The doctor said something along the lines of: "You're a good Jewish boy helping your mom. You're needed here more than there." The doctor classified Hertzel as 4F for hypertension. That doctor later became Hertzel's physician.

Soon after, Hertzel decided he didn't want a job. "I want my own business."

With the help of older relatives who recognized his business acumen and hustle, he opened a store selling TVs just as they were becoming hot items. He juiced up sales with savvy marketing: "I had the television rigged up in the store window so people outside could hear it and stand and watch it," he said.

The real money came not from the sales, but from carrying the note. He'd take $25 down for a $400 set, then collect payments plus interest every week. He also sold Kelvinator refrigerators. He did such a great job moving those that he earned rewards from the company - more trips to Europe.

He did so well that he wanted to buy a nearby furniture store.

"They agreed to the sale, but it did not go through because the seller did not want to sell to a Jew," he said. "They sold it to someone else for less than I'd offered. So I said to the new owner, `I tried to buy this but they wouldn't sell it to me. Do you want to sell it?'"

The new owner saw a chance to make a quick profit and bolt. So he did. Hertzel paid about what he'd originally offered. More importantly, this launched about 40 years of various incarnations of Aron Furniture, owned and operated by Hertzel and Sidney.

Yet real estate appealed to Hertzel as much or perhaps more than furniture. He dabbled in various other investments that caught his eye. Once he and Sidney closed the furniture stores, he sold houses for a while. He stopped in the mid-2000s because it bothered him to see people who made so little getting approved to buy houses so expensive. The subprime mortgage market collapsed soon after.

Never one to brag, he took satisfaction when his business instincts paid off. Mostly because it meant he could share his success with his family.

***

Hertzel loved being Orina's son and a brother to his siblings. He loved being an uncle and a cousin. And, of course, he loved being a husband and father.

He married at 24 and had three children: Cherie, Allison and Ethan. When that relationship ended in divorce, he lost contact with those kids - but not for a lack of trying. Courts weren't kind to fathers in the '60s and '70s, and others he reached out to for help were unable to provide it. His great hope was that his kids would come looking for him. After all, he'd lived in Houston since the 1940s, owned a business with his name on it, and his large family made it even easier for him to be found. If only the internet had existed earlier, shrinking the world so people could reconnect across years and miles, maybe things would've been different. If anyone reading this knows Cherie, Allison and Ethan, please share this with them.

Around 1966, Hertzel went on a blind date with a woman visiting Houston from Mexico City. Shortly after, he married Dorita Cheskes and became father to her children, Jenny and Jacky. In 1970, the couple had a child together, Jaime.

Hertzel's siblings had a combined 17 children, making the family tree more like a forest. He looked forward to every bar/bat mitzvah, wedding and baby naming. He might've been happiest when surrounded by the limbs and branches of the Aron-Wilkenfeld tree; the more, the merrier. (His dad was among two brothers who married Wilkenfeld sisters. Hertzel always said there would've been more, but one of the dads declared enough was enough.)

Many rites of passage were celebrated at Beth Yeshurun. Just as the Aron-Wilkenfeld clan were pioneers at the Goose Greek shul, they became pillars of that congregation upon arriving in Houston. He was a regular at Saturday morning services until the pandemic.

Hertzel and his siblings lived a short drive from each other until Peggy passed away in 2010. Merilee died in 2011, then Sidney in 2015. That made Hertzel the family's elder statesman. As with his understated satisfaction of his business success, he relished that role; when he turned 89, he dropped into conversation that he'd now lived longer than anyone else on his branch of the family tree.

***

Between losing his father at 10 and growing up in the Depression and its aftermath, Hertzel never played or followed sports. It's a funny tidbit considering his son became a sports writer, but also understandable considering how many other things interested him.

Travel may have topped the list, especially seeing the world with family or friends. He particularly enjoyed visiting places rich in history and scenery, better still on a group tour or a cruise. From the 1960s to the '80s, the furniture store he ran was a warehouse with scant air conditioning, so he preferred getting out of the Houston heat every August. He and Sidney also took business trips to destinations such as Italy and Hong Kong, the latter coming only days after he broke his right arm while roller skating.

Although he rarely listened to music, Hertzel enjoyed playing. He long had a piano that he "piddled around on." Then he began playing a harp in the 1970s. He stopped because of a broken part that couldn't be repaired or replaced. Then, in the 2000s - in his 70s - he decided to start again. He even reconnected with his previous teacher, Mary Jane Sinclair, who became a close friend.

Hertzel was handy around the house, although not in the ways that phrase usually implies. He loved growing plants and flowers in the large backyard of his home on South Braeswood, and kneading and braiding dough to make challah. He was skilled with a needle and thread thanks to early career jobs in clothing. (While he never shot hoops with Jaime, he once made him a shiny basketball tank top on a new sewing machine he'd bought.)

Never a flashy person, Hertzel was fond of jewelry, fedoras and newsboy hats, and the occasional splurge: a diamond ring and fur coat when he turned 50, an Alfa Romeo convertible when he turned 60. (It lasted about a year; it wasn't so comfortable with the roof up.)

He supported countless organizations, financially and with his time. He long volunteered at MD Anderson Hospital, where Dorita beat a devastating form of melanoma in the mid-1970s, long before success stories were as common as they are today. His role was going to patients' rooms to bring them things to read and such. In the years when he was still working, he made sure to be there on Thanksgiving and Christmas, so other volunteers could be with their families. Once he retired, he took on more shifts, eventually earning awards for his accumulated hours. Also in retirement, he began working as a mediator. He was honored there, too, for how much time he put in.

The one thing he never figured out was technology. Once he finally figured out his flip phone, he refused to give it up. The farthest he came was learning how to use the Audible app on a Kindle, and wireless headphones, so he could listen to audiobooks. Histories, mysteries and biographies entertained him for hours in his final years.

***

In mid-life, Hertzel's health challenges included a nasty bout with hepatitis and a neurological condition called myasthenia gravis. To treat that, doctors needed to remove a gland near his heart. Since his chest was going to be cracked open, he saw a cardiologist to see whether any tune-up work was needed. Indeed, a bigger problem was avoided as he got multiple bypasses.

The myasthenia flared years later because of anesthesia given during a knee replacement surgery. Other setbacks he overcame include a broken neck suffered when he fell out of bed one night and a broken leg that required the insertion of a titanium rod. He dealt with other heart problems and a Graves' disease in his left eye, all of which he chalked up to what comes with getting old.

A different challenge arrived violently, with the 1-2 punch of the Memorial Day floods in 2015 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017. The floods marked the first time that Braes Bayou expanded into his bayou-facing home on South Braeswood, so he opted to rebuild. Harvey ruined that, so he and Dorita moved into a condo. His favorite part was the view in the middle of the night. He often had trouble sleeping, so he'd go from bed to his favorite chair, where he could be mesmerized by the city lights.

***

Because his 90th birthday came in the throes of the pandemic, Hertzel's family celebrated digitally. About 20 of his closest relatives sent videos telling him how much he meant to them. Because he didn't know how to use a computer, he received a book-sized greeting card with a video player inside. He watched it every day for months. It remained on the table next to him into his final hours.

The end came relatively quickly. Breathing trouble on Labor Day forced him into the hospital. Diagnosed with congestive failure, he ended up having fluid drained from outside his lungs. Breathing comfortably again, he was discharged. A few days later, tests on that fluid found mature B-cell lymphoma. He chose to enter home hospice care the next day.

Hertzel remained sharp and caring to the end. About a half hour after finalizing the purchase of a new car for Dorita, a parting gift that meant as much to him as her, he suffered a bout of terminal agitation. He died hours later, painlessly, surrounded by Dorita, Jaime and beloved daughter-in-law Lori, with the city lights twinkling outside the window.

He's survived by wife Dorita; children Jaime and Lori Aron of Dallas; Jacky and Laura Aron of Advance, North Carolina; Jenny Solomon of Seattle; and grandchildren Rachel Solomon, Michelle Solomon, Zac Aron, Jake Aron and Josh Aron. In addition to his sister Bernadean Rosenblatt, he leaves behind countless family and friends.

He'd want to say thanks to all his doctors, particularly Josh Septimus, David Yao, Yadollah Harati and Silvia Orengo. Special thanks to those who cared for him in his final weeks, from his round-the-clock crew of caregivers (Yoli, Tina, Barbara, Mary and Rosetta) to everyone at Houston Hospice, particularly a nurse named Lincoln who guided us through the difficult final hours.

Hertzel never specified a charity for donations; it was among the conversations still to be had. So support your favorite charity in his honor. He'd like it that way.